I can't remember where I picked this up. I know that Robert Silverberg is a fairly prolific sci-fi author and have never read anything by him. Lost Race of Mars is a Scholastic book, written for late elementary school kids and probably something I would have dug back then. I was hoping to get a teeny taste for Silverberg and more importantly a bit of insight into the kind of sci-fi schoolkids would be reading in 1960 when it was published.

The Chambers are the classic '50s nuclear family, father is a scientist, mother is a homemaker and Sally and Jim keen brother and sister. The year is 2017 and earth has a colony on Mars. Dr. Chambers (the dad) receives a grant to go and study there for a year. There is evidence that there was an ancient race on Mars but most people believe them to be long dead. There are plants, animals and a bit of water, even thin oxygen (either Silverberg was fudging it for a kids book or they really did not have much knowledge about the solar system back then). When the family gets there, they do not receive a friendly welcome. The ethos is one of hard work and practicality and they are seen as freeloaders, using up precious oxygen and resources and not contributing anything tangible. The father struggles to get the equipment he needs. The children are particularly mean and Sally and Jim find themselves ostracized. They decide to sneak out on their own to see if they can find the martians.

It's a fun, quick little read, simplistic and not super realistic. I will slip it into my daughter's shelf and maybe she will chance upon it one day in the future (assuming we aren't dragging a sled with our bare necessities across the wasteland). I will be curious to see what she thinks about it.

Here is a nice blog post giving a bit of history on the book and reference material on Silverberg and the illustrator, Leanard Kessler.

Friday, September 29, 2017

Thursday, September 28, 2017

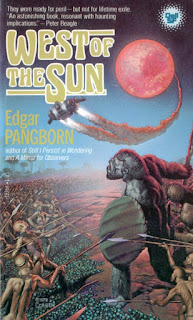

36. West of the Sun by Edgar Pangborn

Lost in the mists of time is the source of my original reason for adding Edgar Pangborn's Davy to my paperback hunting list I keep in my wallet. I found West of the Sun in Victoria and though it wasn't Davy, it is the first Edgar Pangborn I had found, so I decided to buy it. I read it and respected, but not sure if I should keep Davy on my list.

Based on this single novel, I feel I can say that Pangborn is a good writer, intelligent and thoughtful. However, I am not sure if he is really to my style. The story take place in the early 21st century. Earth sends out an exploratory ship and the book begins when that ship finds a livable planet Unfortunately the ship crashes and the crew has to consider living there forever. It is divided into 3 parts: the initial landing. 1 year later and 10 years later. It reminded me a lot of Earth Abides. Much of the story is interacting with the local flora and fauna and meeting the intelligent life (of which there are two kinds, cannibalistic warrior pigmies and super chill solitary ape creatures). Much of, though, is about the crew themselves and how they are going to try and start a new human society while interacting with and developing the existing creatures.

The Prime Directive is definitely violated here, as they bring language and tools and just generally make a massive impact on the part of the planet they landed on. It's an interesting story and a thoughtful exploration of what would be the challenges of landing on and surviving in another world. There is also, unfortunately for me, a lot of long conversations about theories of civlization, much of it in that weird early 60s language that always seems trying to hard to be poetic and clever. I found it particularly annoying that when the natives learn english, they speak it like some upper middle class housewife in a John D. MacDonald suburban thriller. Basically, the ratio of story and characters to ideas about society was way too low for me.

These are my pet peeves and I will still keep an eye out for Davy, but I waver.

Based on this single novel, I feel I can say that Pangborn is a good writer, intelligent and thoughtful. However, I am not sure if he is really to my style. The story take place in the early 21st century. Earth sends out an exploratory ship and the book begins when that ship finds a livable planet Unfortunately the ship crashes and the crew has to consider living there forever. It is divided into 3 parts: the initial landing. 1 year later and 10 years later. It reminded me a lot of Earth Abides. Much of the story is interacting with the local flora and fauna and meeting the intelligent life (of which there are two kinds, cannibalistic warrior pigmies and super chill solitary ape creatures). Much of, though, is about the crew themselves and how they are going to try and start a new human society while interacting with and developing the existing creatures.

The Prime Directive is definitely violated here, as they bring language and tools and just generally make a massive impact on the part of the planet they landed on. It's an interesting story and a thoughtful exploration of what would be the challenges of landing on and surviving in another world. There is also, unfortunately for me, a lot of long conversations about theories of civlization, much of it in that weird early 60s language that always seems trying to hard to be poetic and clever. I found it particularly annoying that when the natives learn english, they speak it like some upper middle class housewife in a John D. MacDonald suburban thriller. Basically, the ratio of story and characters to ideas about society was way too low for me.

These are my pet peeves and I will still keep an eye out for Davy, but I waver.

Monday, September 25, 2017

35. Balconville a play by David Fennario

A friend gave me this play for my birthday and it has been sitting on my shelf for a few years. It's a real artifact from the anglo-Canadian scene during the height of the struggle for independence in Quebec. Well that's what it takes place, but it was written in 1980, so about ten years later, but the issues were certainly still going on in this form back then.

The play takes place in Pointe-St-Charles, a neighbourhood on the other side of the canal from downtown Montreal, one of the earliest working class neighbourhoods and also a place where a lot of the social spirit of Quebec and Montreal was started. The play is set in facing balconies, with two anglophone families on one side and a francophone family on the other. Most of what goes on is street life among the working class people, in french and english: angry teenage daughter, alchoholic unemployed boyfriend, simply delivery guy, tired wives and so on. It's quite entertaining and would probably be quite fun to see live. There is no innate conflict between the french and english, but as the play goes on and when there is conflict about other things, it quite quickly leads to blaming the other side.

It all is leading up to a pretty obvious political sentiment, which is made explicit at the climactic ending when the actors turn to the audience and say "What are we going to do?" in french and english. The answer is obvious in the text, which is stop fighting amongst yourselves and unite to fight the real enemy, the wealthy and the politicians.

I like the sentiment and I generally agree with it, but I can also see how a francophone audience at the time might not take it so positively. This is a very similar kind of dynamic as to what is going on now in the States with all this talk about the poor white people in the flyover states being neglected by the left. Yes, it sucks for everybody who is poor. It sucks even worse to be poor and in a cultural minority. This is something the resentful anglophones never really understood (and to this day you still hear them complain of the discrimination against them here as if the bureaucracy in B.C. or Ontario is somehow super effective and well-managed). So it feels a bit naive and optimistic for Fennario to think that the two solitudes are going to unite while all the advantages were still structurally geared towards english speakers. It's telling that this play has only performed in English theatres (at least according to the book; it may have shown elsewhere since then).

The other interesting thing is that Pointe St-Charles is gentrifying pretty quickly and the people that make up the characters in this play are slowly disappearing from that neighbourhood. It will take a while still but already the struggle and hardships depicted in this play are disappearing (or more likely moving away) and along with them a lot of the spirit and culture here too, to be replaced by professional families who organize "playdates" and worry about safety.

The play takes place in Pointe-St-Charles, a neighbourhood on the other side of the canal from downtown Montreal, one of the earliest working class neighbourhoods and also a place where a lot of the social spirit of Quebec and Montreal was started. The play is set in facing balconies, with two anglophone families on one side and a francophone family on the other. Most of what goes on is street life among the working class people, in french and english: angry teenage daughter, alchoholic unemployed boyfriend, simply delivery guy, tired wives and so on. It's quite entertaining and would probably be quite fun to see live. There is no innate conflict between the french and english, but as the play goes on and when there is conflict about other things, it quite quickly leads to blaming the other side.

It all is leading up to a pretty obvious political sentiment, which is made explicit at the climactic ending when the actors turn to the audience and say "What are we going to do?" in french and english. The answer is obvious in the text, which is stop fighting amongst yourselves and unite to fight the real enemy, the wealthy and the politicians.

I like the sentiment and I generally agree with it, but I can also see how a francophone audience at the time might not take it so positively. This is a very similar kind of dynamic as to what is going on now in the States with all this talk about the poor white people in the flyover states being neglected by the left. Yes, it sucks for everybody who is poor. It sucks even worse to be poor and in a cultural minority. This is something the resentful anglophones never really understood (and to this day you still hear them complain of the discrimination against them here as if the bureaucracy in B.C. or Ontario is somehow super effective and well-managed). So it feels a bit naive and optimistic for Fennario to think that the two solitudes are going to unite while all the advantages were still structurally geared towards english speakers. It's telling that this play has only performed in English theatres (at least according to the book; it may have shown elsewhere since then).

The other interesting thing is that Pointe St-Charles is gentrifying pretty quickly and the people that make up the characters in this play are slowly disappearing from that neighbourhood. It will take a while still but already the struggle and hardships depicted in this play are disappearing (or more likely moving away) and along with them a lot of the spirit and culture here too, to be replaced by professional families who organize "playdates" and worry about safety.

34. Thongor in the City of Magicians

More Thongor! I am reading these because I found a pretty nice set of old British paperbacks at Chainon. Unfortunately, it didn't include the one before this one (Thongor against the Gods, I believe), so I missed another most certainly epic chapter in Thongor's domination of all things vile in Lemuria. Lin Carter is very conscious of this possibly happening as much of the start of Thongor in the City of Magicians is a recap of all of Thongor's previous adventures, as well as listing out all the secondary characters and the political situation. The problem is there is a ton of secondary characters and their names all sound the same and they are all exemplaries of their brand of heroism and manliness. Likewise with the various cities. It's very hard to distinguish between them all. This is real nerdery here. Probably had I read these when I was into this stuff, I would have written it all out, drawn maps and so on. In my late 40s, it becomes a real slog.

When you finally get through all that, the story does get quite fun. This time, we learn about the source of all the nasty druids and alchemists who had been taking over the good cities. It's the city of Zaar, far to the south of Lemuria, run by nine evil wizards and surrounded by black marble walls (that also hold back the crashing waves of the Pacific). Thongor and his people head in that direction to mine some precious stones filled with sun energy and of course he gets captured. Lots of ass-kicking ensues and great descriptions of corrupt magic and its practitioners.

This book really emphasizes that Lemuria is from earth's past and will sink into the ocean. It even suggests that the continent has been weakened by all the meddling with dark magics, a bit of a climate change metaphor from back in the day.

Finishing this, I also realized that maybe Carter adds all the nerdery to pad the book out, because it's barely a novel as is and would almost be more of a short story.

When you finally get through all that, the story does get quite fun. This time, we learn about the source of all the nasty druids and alchemists who had been taking over the good cities. It's the city of Zaar, far to the south of Lemuria, run by nine evil wizards and surrounded by black marble walls (that also hold back the crashing waves of the Pacific). Thongor and his people head in that direction to mine some precious stones filled with sun energy and of course he gets captured. Lots of ass-kicking ensues and great descriptions of corrupt magic and its practitioners.

This book really emphasizes that Lemuria is from earth's past and will sink into the ocean. It even suggests that the continent has been weakened by all the meddling with dark magics, a bit of a climate change metaphor from back in the day.

Finishing this, I also realized that maybe Carter adds all the nerdery to pad the book out, because it's barely a novel as is and would almost be more of a short story.

Friday, September 22, 2017

33. The Levanter by Eric Ambler

I went through a big re-read of Eric Ambler's pre-WWII books and really enjoyed them. My memory of his post-WWII books were less positive and I wasn't so enthused to jump into this book. I think I was concerned that they would be suffer from that weird 70s masculinity of that generation of British writers. I also suspected they may be have been a bit too subtle for my younger mind.

I am happy to report, that at least with the Levanter, my concerns were entirely unfounded. I do see why my younger self didn't find it quite as thrilling as say Desmond Bagley or Michael Gilbert. It's the richness of the detail, the complexity of character, the description of region that are all done so well that make this book so great. It also has a slow, simmering tension that really grabs onto you and forces you to keep turning the pages to find out what happens. I think, though, that all of those positive aspects are more effective with an older reader. There are pages and pages, for instance, of the history of a family company in the mediterranean. I soaked it up, but I could see others thinking it was boring.

The structure is also interesting. At it's core, The Levanter has a simple plot. A businessman in the middle east is forced to participate in a terrorist plot and has to use his wits to prevent it, save himself, his mistress and his business. However, it takes a while for the reader to figure it out, as it begins in the future and jumps between the viewpoints of said businessman and a journalist and seems, at first, to be more about a well-known lesser Palestinian terrorist. Once the structure settles down and you stick with the businessman's narrative, you, as I said above, really get stuck in. He accidently discovers that one of his night watchmen is this terrorist leader and has been using his battery factory to build his devices and train his men. The terrorist then forces him to join them and the rest of the book is his attempt to find a way out.

Really great stuff. The businessman himself, though named Michael Howell, is really a mutt of the colonial middle east, English from three generations back but now mixed with Turkish and Greek Cypriot blood, educated in British public schools but fluent in Arabic, Greek and a few other languages. He's a great character, privileged and a bit smarmy but also skilled and competent. There is implicit bias here, for sure. All the middle eastern characters are either terrorists, manipulative civil servants or cruel policemen. Even the Israelis are demonstrated as being difficult. The only truly reasonable people are the protagonist, his mistress and an American journalist. We will see if this bias plays out in other Ambler books.

I am happy to report, that at least with the Levanter, my concerns were entirely unfounded. I do see why my younger self didn't find it quite as thrilling as say Desmond Bagley or Michael Gilbert. It's the richness of the detail, the complexity of character, the description of region that are all done so well that make this book so great. It also has a slow, simmering tension that really grabs onto you and forces you to keep turning the pages to find out what happens. I think, though, that all of those positive aspects are more effective with an older reader. There are pages and pages, for instance, of the history of a family company in the mediterranean. I soaked it up, but I could see others thinking it was boring.

The structure is also interesting. At it's core, The Levanter has a simple plot. A businessman in the middle east is forced to participate in a terrorist plot and has to use his wits to prevent it, save himself, his mistress and his business. However, it takes a while for the reader to figure it out, as it begins in the future and jumps between the viewpoints of said businessman and a journalist and seems, at first, to be more about a well-known lesser Palestinian terrorist. Once the structure settles down and you stick with the businessman's narrative, you, as I said above, really get stuck in. He accidently discovers that one of his night watchmen is this terrorist leader and has been using his battery factory to build his devices and train his men. The terrorist then forces him to join them and the rest of the book is his attempt to find a way out.

Really great stuff. The businessman himself, though named Michael Howell, is really a mutt of the colonial middle east, English from three generations back but now mixed with Turkish and Greek Cypriot blood, educated in British public schools but fluent in Arabic, Greek and a few other languages. He's a great character, privileged and a bit smarmy but also skilled and competent. There is implicit bias here, for sure. All the middle eastern characters are either terrorists, manipulative civil servants or cruel policemen. Even the Israelis are demonstrated as being difficult. The only truly reasonable people are the protagonist, his mistress and an American journalist. We will see if this bias plays out in other Ambler books.

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

32. The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi

My brother-in-law got me this last xmas and I had put it away for a time when I was ready for some good, modern sci-fi. I actually got started on it this Spring, but couldn't get into it. In my current new reading resurgence, I jumped right in. On the back of the book, the blurb says it is hard science fiction. I think that is a mischaracterization. It's definitely high-level, with some technical ideas that require a bit of understanding (like public private key encryption). I would consider it more transhuman. We are out in space with quantum nanotechnology that allows people to take over different bodies and space battles that are complex combinations of nuclear firepower and code attacks.

It takes a while to figure out what is going on. The protagonist is a thief who gets sprung from a space jail where he keeps having to engage in a prisoner's dilemma with the other prisoners (and keeps dying). A space warrior chick working for a goddess needs him to do a mission on Oubliette, which is the civilization on Mars. Things there are really complicated and I won't even go into it, suffice it to say that it's pretty cool if you are into that kind of thing.

I'm just a little old and lazy now and while I appreciate the author not explaining a lot of things, it also made it harder to get into. In the end, I think I more or less figured out the major plot. Stories where technology is so advanced can sometimes lack emotional connection with the characters, especially when they are constantly rewriting their own identities and memories. I found that to be the case here. Nonetheless, the situation and tech was so cool that I quite enjoyed it. Of course, it turns out to be a trilogy and probably one I will have to eventually seek out (at which point I will have most likely forgotten what happened in the first book. Sigh.)

[Completely irrelevant side note: the title of this book is accurate and it makes me think of another title that totally bugs the shit out of me, the movie Quantum of Solace. What the fuck does that even mean? I don't dislike Daniel Craig but his Bonds are probably the worst of them all and that stupid, meaninglessly pretentious title perfectly exemplifies why.]

It takes a while to figure out what is going on. The protagonist is a thief who gets sprung from a space jail where he keeps having to engage in a prisoner's dilemma with the other prisoners (and keeps dying). A space warrior chick working for a goddess needs him to do a mission on Oubliette, which is the civilization on Mars. Things there are really complicated and I won't even go into it, suffice it to say that it's pretty cool if you are into that kind of thing.

I'm just a little old and lazy now and while I appreciate the author not explaining a lot of things, it also made it harder to get into. In the end, I think I more or less figured out the major plot. Stories where technology is so advanced can sometimes lack emotional connection with the characters, especially when they are constantly rewriting their own identities and memories. I found that to be the case here. Nonetheless, the situation and tech was so cool that I quite enjoyed it. Of course, it turns out to be a trilogy and probably one I will have to eventually seek out (at which point I will have most likely forgotten what happened in the first book. Sigh.)

[Completely irrelevant side note: the title of this book is accurate and it makes me think of another title that totally bugs the shit out of me, the movie Quantum of Solace. What the fuck does that even mean? I don't dislike Daniel Craig but his Bonds are probably the worst of them all and that stupid, meaninglessly pretentious title perfectly exemplifies why.]

Friday, September 15, 2017

31. Tigers of the Sea by Robert E. Howard

I believe it was Cormac Mac Art that my friend Jason first discovered way back in the day when we were nerdy teenagers and told me that there were characters other than Conan written by Howard. It was quite a revelation at the time! However, I never actually read anything other than Conan in all these years, so I was glad to find this book (and a Bran Mak Morn one as well to be read soon) at my local thrift store.

There are good and bad elements about reading a series of pulp stories about the same character. It's cool to have it as a historical artifact and its very existence is thanks to Richard L. Tierney. He put the collection together and had it published in 1975. He also wrote a very helpful introduction that is a survey of all the various characters that Howard created in old Europe and how they connect together in various historical periods. I would have liked a bit more detail on the actual publication dates and sources, but the history is really helpful to ground the stories and give you clues to hunt down his other books.

On the other hand, there is a certain sameness to three of the stories here. Cormac Mac Art is a badass Erin warrior who has travelled and warred all over the post-Roman British isles who is also very clever. Each story has him and his pirate chief Wulfere sneaking into some enemy camp, either with physical subterfuge or in disguise, getting involved in some greater conflict, kicking a ton of ass and then getting out with the booty. The ass-kicking is rip-roaring, heavy physical stuff (gigantic axes smashing through helms kind of thing) which I really enjoy. After two stories of it, though, one needs a bit of a break. It pains me to write this but I was even slightly bored at a couple points (sorry, sorry, Robert E. Howard). It's like three pot roasts in a row. Ideally, you have had a shitty day at work dealing with the whinging and the incompetent and you go home, have an ale and read one of these stories about how one really deals with lesser men to get your head straight again.

The last story, "The Temple of Abomination" was not completed and was a breath of fresh air from all the vikings and their stockades, with an ancient dark druid and the fetid, corrupt creatures he commands.

There are good and bad elements about reading a series of pulp stories about the same character. It's cool to have it as a historical artifact and its very existence is thanks to Richard L. Tierney. He put the collection together and had it published in 1975. He also wrote a very helpful introduction that is a survey of all the various characters that Howard created in old Europe and how they connect together in various historical periods. I would have liked a bit more detail on the actual publication dates and sources, but the history is really helpful to ground the stories and give you clues to hunt down his other books.

On the other hand, there is a certain sameness to three of the stories here. Cormac Mac Art is a badass Erin warrior who has travelled and warred all over the post-Roman British isles who is also very clever. Each story has him and his pirate chief Wulfere sneaking into some enemy camp, either with physical subterfuge or in disguise, getting involved in some greater conflict, kicking a ton of ass and then getting out with the booty. The ass-kicking is rip-roaring, heavy physical stuff (gigantic axes smashing through helms kind of thing) which I really enjoy. After two stories of it, though, one needs a bit of a break. It pains me to write this but I was even slightly bored at a couple points (sorry, sorry, Robert E. Howard). It's like three pot roasts in a row. Ideally, you have had a shitty day at work dealing with the whinging and the incompetent and you go home, have an ale and read one of these stories about how one really deals with lesser men to get your head straight again.

The last story, "The Temple of Abomination" was not completed and was a breath of fresh air from all the vikings and their stockades, with an ancient dark druid and the fetid, corrupt creatures he commands.

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

30. First on the Moon by Jeff Sutton

Golden Age sci-fi is not totally my bag. I can't remember where I got this book but I really liked the bold, colourful cover and it was in good condition. I thought it was going to be a fantastic gee-whiz space story, but it is actually much more akin to a hard sci-fi attempt to realistically imagine in 1958 what a race to the moon would look like.

It takes place during the height of the cold war and is told from the perspective of an elite pilot brought into a top secret training program. Paranoia is everywhere, to the point that he is pulled from his last date before launch because two previous pilots were killed in staged accidents. He and his date are replaced with doubles (whom we later learn are also killed). He is then led to the real rocket (the one he had been training on turns out to have been a duplicate to further fool the enemy) and meets his crew of three. It's a tense, steady read. A bit dry at times, but with enough suspense and even some characterization to keep me hooked. They go to the moon, have to deal with all the very real issues of survival there as well as the commies who do all kinds of dastardly things. They send a missile while they are in flight, they send another rocket themselves. The whole point is that the country that first establishes a succesful person on the moon gets to claim it for their own in the eyes of the UN. Once on the planet, the commander also learns that one of his men is a double agent who is sabotaging the mission.

It kind of felt like what I imagine The Martian was like, but from a 1958 perspective. Jeff Sutton did many things in his life (including writing quite a few science fiction novels), among them working on survival issues for high-altitude pilots, so he knew his stuff. Solid read.

It takes place during the height of the cold war and is told from the perspective of an elite pilot brought into a top secret training program. Paranoia is everywhere, to the point that he is pulled from his last date before launch because two previous pilots were killed in staged accidents. He and his date are replaced with doubles (whom we later learn are also killed). He is then led to the real rocket (the one he had been training on turns out to have been a duplicate to further fool the enemy) and meets his crew of three. It's a tense, steady read. A bit dry at times, but with enough suspense and even some characterization to keep me hooked. They go to the moon, have to deal with all the very real issues of survival there as well as the commies who do all kinds of dastardly things. They send a missile while they are in flight, they send another rocket themselves. The whole point is that the country that first establishes a succesful person on the moon gets to claim it for their own in the eyes of the UN. Once on the planet, the commander also learns that one of his men is a double agent who is sabotaging the mission.

It kind of felt like what I imagine The Martian was like, but from a 1958 perspective. Jeff Sutton did many things in his life (including writing quite a few science fiction novels), among them working on survival issues for high-altitude pilots, so he knew his stuff. Solid read.

Monday, September 11, 2017

29. The Case of the Vanishing Boy by Alexander Key

When I was a kid in elementary school, Escape from Witch Mountain came out. I'm still not sure if it was a movie or a TV special, but everybody was talking about it. I somehow saw at least an image from it and remember having a powerful crush on the girl. I never did see it. We didn't have TV and for some reason it never got on my parents' radar, but like a lot of media that I didn't see, I pretended that I had to be part of the conversation (Mad Magazine parodies were the best for this).

When I was a kid in elementary school, Escape from Witch Mountain came out. I'm still not sure if it was a movie or a TV special, but everybody was talking about it. I somehow saw at least an image from it and remember having a powerful crush on the girl. I never did see it. We didn't have TV and for some reason it never got on my parents' radar, but like a lot of media that I didn't see, I pretended that I had to be part of the conversation (Mad Magazine parodies were the best for this).I don't remember where I found this book, but I thought I should check it out. I wouldn't be surprised if there is some small re-discovery of Key's work, because this stuff falls squarely in the same genre as the successful Stranger Things series on Netflix. Adolescent kids with powers who discover malfeasance among nasty, scientific adults and have to deal with it mostly on their own. In this case, there are also some good adults, who are of course, self-consciously non-conformist.

This is actually Key's last book (he died in 1979). The story here is about Jan, a boy who wakes up on a commuter train with no memory of who he is or where he came from but that he is running. He meets a blind girl on the train who spots him as somebody in trouble and the adventure begins (or continues). I really enjoyed the in media res beginning. I sort of figured most of the mystery out (minus the details) quite quickly. It's a tight read, quite thrilling and enjoyable with real stakes and action. I will see if my 12-year old nephew finds it interesting. I think I would like to check out Escape from Witch Mountain and maybe even the original movie, just so I can talk about it without making stuff up.

Sunday, September 10, 2017

28. Thongor of Lemuria

Part two of the Thongor saga, which is not always easy to know as the titles all kind of sound the same. I need at some point to make a reference list. The first one is called The Wizard of Lemuria and the second Thongor of Lemuria and on the back of the edition I have, where they list the other titles, they don't specify if they are in order (and they call it "the saga of Thongor of Lemuria" but that isn't the name of the first book, argh!). I remember as a young nerd in the late '70s and early '80s how it was so hard to find out any info on things (like which Star Trek episode came from which season, or what all the Star Wars cards were and so on). On the one hand, this lack of information probably is what gives me my book-hunting drive today. On the other, it seems damned lazy and cheap by the publishers at the time, who knew they were marketing to anal-retentive nerds and should have given us the data we needed.

Anyhow, this is another chapter in Thongor's ass-kicking life. It starts off immediately after where the last one left off, with Thongor, the hot babe Sumia and his less extraordinary but still capable soldier friend Karm Karvus on the airship. They hit an electrical storm and fall into the ocean and all kinds of shit happens. It starts out at first with them being on an unknown jungle isle, fighting local flora, fauna and primitives, but we quite quickly get back to the bigger geopolitical plot of decadent, evil men taking over kingdoms and cities and fucking with Thongor.

Like the first book, at first I was a bit bored and found it all too simplistic and derivative and then things got quite weird and excessive and I was once again in for the ride. I do find disappointing the depiction of the jungle savages. It's not quite as blatantly racist as Howard, but still has the boring trope that being primitive means not only being less civilized but also arbitrarily crueler and genetically inferior. Plus, they are dark and apelike. I get the sexism in these books, written in 1966, but you think Lin Carter might have been just slightly more aware than the pulp writers of the thirties. Sentences like "Scores of the shaggy Beastmen and their unlovely mates and equally repulsive cubs crawled from the huts to watch the procession" bum me out. I'm not expecting a post-colonial deconstruction of the native "other" here, just maybe a bit more sense that a bunch of natives living in the jungle might actually have a reason for doing what they are doing.

The more civilized badguys in this book are, on the other hand, quite entertaining and creative and their evil is due to their own character flaws (greed, ambition, etc.) rather than any innate genetic characteristics. The torturer whose body is bubbling with disease, the corpulent scientist vampire who sits naked in his techno-chair feeding on the blood of his people, these guys often have weak and cruel lips. Good stuff.

I am just going to keep on cruising through this saga. I found a bunch of Thongors at Chainon from Tandem, a British press. The image above is my scan. Oh yeah, there re so many names of beasts, places and especially characters and they all kind of use the same structure that I couldn't really keep them straight.

Anyhow, this is another chapter in Thongor's ass-kicking life. It starts off immediately after where the last one left off, with Thongor, the hot babe Sumia and his less extraordinary but still capable soldier friend Karm Karvus on the airship. They hit an electrical storm and fall into the ocean and all kinds of shit happens. It starts out at first with them being on an unknown jungle isle, fighting local flora, fauna and primitives, but we quite quickly get back to the bigger geopolitical plot of decadent, evil men taking over kingdoms and cities and fucking with Thongor.

Like the first book, at first I was a bit bored and found it all too simplistic and derivative and then things got quite weird and excessive and I was once again in for the ride. I do find disappointing the depiction of the jungle savages. It's not quite as blatantly racist as Howard, but still has the boring trope that being primitive means not only being less civilized but also arbitrarily crueler and genetically inferior. Plus, they are dark and apelike. I get the sexism in these books, written in 1966, but you think Lin Carter might have been just slightly more aware than the pulp writers of the thirties. Sentences like "Scores of the shaggy Beastmen and their unlovely mates and equally repulsive cubs crawled from the huts to watch the procession" bum me out. I'm not expecting a post-colonial deconstruction of the native "other" here, just maybe a bit more sense that a bunch of natives living in the jungle might actually have a reason for doing what they are doing.

The more civilized badguys in this book are, on the other hand, quite entertaining and creative and their evil is due to their own character flaws (greed, ambition, etc.) rather than any innate genetic characteristics. The torturer whose body is bubbling with disease, the corpulent scientist vampire who sits naked in his techno-chair feeding on the blood of his people, these guys often have weak and cruel lips. Good stuff.

I am just going to keep on cruising through this saga. I found a bunch of Thongors at Chainon from Tandem, a British press. The image above is my scan. Oh yeah, there re so many names of beasts, places and especially characters and they all kind of use the same structure that I couldn't really keep them straight.

Thursday, September 07, 2017

27. The Furies by Keith Roberts

I found this at Chainon, a thrift store here that is a fundraiser/job provider for a woman's shelter (called Chainon) and support organization. They have a small but decent english fiction section and while it doesn't change much, every now and then you can find a few gems there. They re-arranged the place earlier this year and right afterwards there was a minor treasure trove of old paperbacks, including a bunch of Thongors and this book, which I grabbed almost purely because it was such a beautiful old paperback. I did not have high expectations.

The subjet matter is certainly in my wheelhouse. Gigantic wasps take over the world. It also is a pretty good book. I would have been happy to have found it even if it were more trashy and less well written, simply because The Furies definitely can be categorized as a post-apocalyptic book. Happily, it turned out to be a pretty good read.

The hero is an illustrator who recently bought a place in the country and has a pretty good life, kind of just enjoying things including a not-expected professional and financial success (that allowed him to buy the house) and a great dane. He also meets a young girl who is vacationing in the area and they become friends, taking the dog for long walks. Then giant wasps start attacking in the area. At first it is sporadic, but then it turns into an all-out assault. At the same time, there are two major nuclear tests that set off massive global earthquakes. The end result is a split and ruptured england and gigantic wasps everywhere, killing humans as efficiently as possible.

This is already a lot of fun but it gets a lot deeper and weirder. I won't reveal too much more of the plot, but there is great survival stuff and rich exploration into what the wasps are doing. It's quite tough. Punches are not pulled, though it is all done with a lot of British stiff upper lip. It's really quite epic. This paperback had small type and small margins so it was deceptively thin, but really could have been a much thicker book.

It's not perfect. There is a bit too much of jumping into omniscient explanation of what is going on. These explanations satisfy one's curiousity, but feel a bit unnatural and take you out of the flow of the survival narrative, which is otherwise quite gripping. Still, I am very happy to add this to my library.

The subjet matter is certainly in my wheelhouse. Gigantic wasps take over the world. It also is a pretty good book. I would have been happy to have found it even if it were more trashy and less well written, simply because The Furies definitely can be categorized as a post-apocalyptic book. Happily, it turned out to be a pretty good read.

The hero is an illustrator who recently bought a place in the country and has a pretty good life, kind of just enjoying things including a not-expected professional and financial success (that allowed him to buy the house) and a great dane. He also meets a young girl who is vacationing in the area and they become friends, taking the dog for long walks. Then giant wasps start attacking in the area. At first it is sporadic, but then it turns into an all-out assault. At the same time, there are two major nuclear tests that set off massive global earthquakes. The end result is a split and ruptured england and gigantic wasps everywhere, killing humans as efficiently as possible.

This is already a lot of fun but it gets a lot deeper and weirder. I won't reveal too much more of the plot, but there is great survival stuff and rich exploration into what the wasps are doing. It's quite tough. Punches are not pulled, though it is all done with a lot of British stiff upper lip. It's really quite epic. This paperback had small type and small margins so it was deceptively thin, but really could have been a much thicker book.

It's not perfect. There is a bit too much of jumping into omniscient explanation of what is going on. These explanations satisfy one's curiousity, but feel a bit unnatural and take you out of the flow of the survival narrative, which is otherwise quite gripping. Still, I am very happy to add this to my library.

Wednesday, September 06, 2017

26. The Blue Hawk by Peter Dickinson

A neat little fantasy novel from 1976 about a boy priest (named Tron, 6 years before the movie) in an isolated religion-bound kingdom. He gets a sign from the gods at an important ritual which he distrupts, thus dooming the king to death. He feels compelled to take the hawk that was to be sacrificed for the king. As it turns out, he was actually being manipulated by the cabal of elderly priests in their machinations to maintain their political strength over the king and the military, who want to open the country up. It's pretty neat as you the reader and the boy discover the world and the political machinations as well as starting to see that while he was manipulated, it's not clear if it was the priests or actually the gods themselves who may be playing a very different game.

A neat little fantasy novel from 1976 about a boy priest (named Tron, 6 years before the movie) in an isolated religion-bound kingdom. He gets a sign from the gods at an important ritual which he distrupts, thus dooming the king to death. He feels compelled to take the hawk that was to be sacrificed for the king. As it turns out, he was actually being manipulated by the cabal of elderly priests in their machinations to maintain their political strength over the king and the military, who want to open the country up. It's pretty neat as you the reader and the boy discover the world and the political machinations as well as starting to see that while he was manipulated, it's not clear if it was the priests or actually the gods themselves who may be playing a very different game.Very cool story for young and old alike.

Tuesday, September 05, 2017

25. Too Mini Murders by Patrick Morgan

Another book in the Operation Hang Ten series about surfing detective/undercover agent Bill Cartwright. I am going to have to go back and check the reviews of the other Operation Hang Ten's that I read (I think two). I don't remember them being as nasty as this one. It really leans heavily on the pornographic mysogyny and it crossed the line for me and left a gross taste in my mouth that the redeeming features wasn't quite able to wash away.

Also, I get that Cartwright is mellow, but here he is downright negligent. A young girl, whose life is threatened, comes to Cartwright's trailer for help. He of course beds her (and satisfies her profoundly in a way none of her previous partners could even come close to doing). The next day, he leaves her in the trailer and tells her to not answer the door for anybody. Of course, the bad guys come and she answers the door. Cartwright doesn't get back until late that evening and doesn't even do anything when he discovers her missing. He goes to the beach the next day! She of course gets brutally raped, tortured and murdered.

There is one interesting passage where he goes to a drag strip and talks about the professionalization of drag racing, how it started out as amateurs in their garage but as the big car companies got involved, became more and more competitive and the little hobbyists slowly got squeezed out or forced to do illegal drag racing. A lot of the philosophy of the book is the individual, free from constraints of the establishment (that is Cartwright's life philosophy to the point that he somehow justifies his violence against criminals in that they, even more than "the man" risk limiting his vagabond lifestyle).

I went back and read the two other reviews and it does sound like the sexual violence in this one is particularily extreme. I'll be wary but keep an eye out for these just because the cover is so cool.

Also, here is the kind of passage that I think reveals the deep-seated social conservatism at the heart of these novels (that I discussed in more depth in my review of The Freaked-Out Strangler). :

Holy shit, that is over the top.

Also, I get that Cartwright is mellow, but here he is downright negligent. A young girl, whose life is threatened, comes to Cartwright's trailer for help. He of course beds her (and satisfies her profoundly in a way none of her previous partners could even come close to doing). The next day, he leaves her in the trailer and tells her to not answer the door for anybody. Of course, the bad guys come and she answers the door. Cartwright doesn't get back until late that evening and doesn't even do anything when he discovers her missing. He goes to the beach the next day! She of course gets brutally raped, tortured and murdered.

There is one interesting passage where he goes to a drag strip and talks about the professionalization of drag racing, how it started out as amateurs in their garage but as the big car companies got involved, became more and more competitive and the little hobbyists slowly got squeezed out or forced to do illegal drag racing. A lot of the philosophy of the book is the individual, free from constraints of the establishment (that is Cartwright's life philosophy to the point that he somehow justifies his violence against criminals in that they, even more than "the man" risk limiting his vagabond lifestyle).

I went back and read the two other reviews and it does sound like the sexual violence in this one is particularily extreme. I'll be wary but keep an eye out for these just because the cover is so cool.

Also, here is the kind of passage that I think reveals the deep-seated social conservatism at the heart of these novels (that I discussed in more depth in my review of The Freaked-Out Strangler). :

Every beach town had its share of night people. He didn't know what they did, it looked like they just cruised around when all the bars closed, crawling up and down side streets. Most were either queer or lesbian. Maybe they looked for easy marks. They sat low in the seats, holding cigarettes between thumb and index finger, dull lifeless eyes searching sidewalks. Feminine men and masculine women.

Holy shit, that is over the top.

Monday, September 04, 2017

24. R.U.R (Rossum's Universal Robots) by Karel Capek

Okay, this is actually a play and only takes an hour or two to read, but I am counting it, damnit! I read this for the G+ Tabletop Roleplayers Book Club, so if you really want to see some nerds in action, you can check out the discussion on this book at the community there.

I loved The War with the Newts and was happy to have another chance to read something else by Capek. I am grateful as well that reading this play spurred me to read about the man himself, who was an interesting and important European intellectual in the first half of the twentieth century. He died in 1938 due to complications from pneumonia due to a lifelong spinal cord problem, but maybe he was lucky as he was #2 on the Nazi's list of people to suppress in Czechoslovakia. When they discovered he was already dead in occupied Czechoslovakia, they interrogated his wife. Later, his brother, a successful artist and collaborator with Karel, died in a concentration camp. 10 years ago, it seemed easy to write whatever you want in North America and atrocities like what happened to the Capek's and others seem in the distant past. With today's climate of growing populist fascism, the choices one makes about what one writes down for others to see becomes slightly more real. It is good to reminded of that.

I was a bit disappointed in the play. I do appreciate that an actual interpretation on stage would have filled in a lot that is implied in the text. As it stands on paper, I found it too abstract and simplistic. What I loved about The War with the Newts was that while it also dealt in big ideas and there weren't any real characters to connect with, the events were so detailed that it all felt very realistic. With R.U.R. we really are in the realm of theatre and allegory and it is all a bit distancing for me. The characters are representations of their area of work or their role in society, so there is the inventor, the accountant, the mechanic and so on. The only women, Helena, who is central to the story is also just that, a woman. All the other men are in love with her immediately.

As a story, it did not move me much. I would love to see it performed one day, as I suspect a lot of richness that is lacking in the text (probably deliberately) would be filled in. And the ideas it does touch on our quite interesting. It's funny as well. Here is a good example:

HALLEMEIER

It was a great thing to be a man. There was something immense about it.

FABRY

From man's thought and man's power came this light, our last hope.

HALLEMEIER

Man's power! May it keep watch over us.

ALQUIST

Man's power.

DOMIN

Yes! A torch to be given from hand to hand, from age to age, forever!

The lamp goes out.

It is well worth reading and since it is in the public domain and is very short, you can do so right now! Here is a handy link to a pdf of the play.

I loved The War with the Newts and was happy to have another chance to read something else by Capek. I am grateful as well that reading this play spurred me to read about the man himself, who was an interesting and important European intellectual in the first half of the twentieth century. He died in 1938 due to complications from pneumonia due to a lifelong spinal cord problem, but maybe he was lucky as he was #2 on the Nazi's list of people to suppress in Czechoslovakia. When they discovered he was already dead in occupied Czechoslovakia, they interrogated his wife. Later, his brother, a successful artist and collaborator with Karel, died in a concentration camp. 10 years ago, it seemed easy to write whatever you want in North America and atrocities like what happened to the Capek's and others seem in the distant past. With today's climate of growing populist fascism, the choices one makes about what one writes down for others to see becomes slightly more real. It is good to reminded of that.

I was a bit disappointed in the play. I do appreciate that an actual interpretation on stage would have filled in a lot that is implied in the text. As it stands on paper, I found it too abstract and simplistic. What I loved about The War with the Newts was that while it also dealt in big ideas and there weren't any real characters to connect with, the events were so detailed that it all felt very realistic. With R.U.R. we really are in the realm of theatre and allegory and it is all a bit distancing for me. The characters are representations of their area of work or their role in society, so there is the inventor, the accountant, the mechanic and so on. The only women, Helena, who is central to the story is also just that, a woman. All the other men are in love with her immediately.

As a story, it did not move me much. I would love to see it performed one day, as I suspect a lot of richness that is lacking in the text (probably deliberately) would be filled in. And the ideas it does touch on our quite interesting. It's funny as well. Here is a good example:

HALLEMEIER

It was a great thing to be a man. There was something immense about it.

FABRY

From man's thought and man's power came this light, our last hope.

HALLEMEIER

Man's power! May it keep watch over us.

ALQUIST

Man's power.

DOMIN

Yes! A torch to be given from hand to hand, from age to age, forever!

The lamp goes out.

It is well worth reading and since it is in the public domain and is very short, you can do so right now! Here is a handy link to a pdf of the play.

Sunday, September 03, 2017

23. Cyteen by C.J. Cherryh

I almost bailed on this book. It was part of the haul that I found down the street from me (mainly the Pelecanos and Lehanes but a few sci-fis as well) and the one that I almost didn't take. It's pretty big (678 pages) and jumps right in to a ton of politics and names and I got lost quickly. I found myself annoyed at the nerdiness (it felt like it was written for the kind of audience that thrives on details that immerse in a setting rather than a human narrative). Fortunately, I had read everything else I brought with me (this was partially planned) and had to come back to it. I am glad I did. It does settle down into a very human, really fair to say deeply human story that while not totally satisfying at the end, takes the reader on a rich journey and makes you think a lot about family and the future of humanity.

The story takes place in the distant future where earth has colonized the stars. There is now earth and and Alliance (which I think are the planets still allied with earth) and then the Union, which is a group that has gone farther out into space and separated in a war from the Alliance. The political capital of the Union is the planet Cyteen. On Cyteen is also a super important institute, Reseune, who developed the cloning technology that has been crucial to humanity's colonization of the stars. The Union is divided into several different political representations (Military, Commerce, Citizens, Industry, etc.) of which Reseune basically controls Science. The politics are roughly competition between the Expansionists who want humanity to keep colonizing space and expanding and the Abolitionists who are against cloning and expansion and the Centrists.

Reseune is led by Ariane Emory, a powerful, superior matriarch. Her advanced intelligence (technical, social and political) is demonstrated early on as well as her many enemies, including another brilliant scientist, Jordan Warrick and his son/clone Justin. Early on in the book, she is murdered. Her family and the political bloc that she represented decides to clone her and grow her replicate up in an environment as close as possible to the original one and her growth and relationship with Justin is the main part of the story for most of the book.

See, it's a lot to explain and I am really glossing over it. The issues that come up are really interesting. Do you hate the child clone of the person who totally fucked you over as an adult? How does a clone react slowly learning about their genetic mirror image and predecessor? And what are the risks of a human society that can clone itself to make beings of various skill levels and psychological stabilities? Cherryh really thinks these things through in Cyteen and it's pretty fascinating stuff. It's also really gripping. You get caught up in it and the readers emotional responses to characters get thoroughly twisted around as you learn different aspects of well-detailed characters. It won the Hugo and I think it deserved it.

Honestly, that I almost gave up on the book in the first twenty pages, I blame on the publisher. This edition had one really crappy map of the planet of Cyteen, which you don't even need. There are only two cities they visit anyways. What it needed was a political map and glossary, so you can quickly figure out who all the players are.

The story takes place in the distant future where earth has colonized the stars. There is now earth and and Alliance (which I think are the planets still allied with earth) and then the Union, which is a group that has gone farther out into space and separated in a war from the Alliance. The political capital of the Union is the planet Cyteen. On Cyteen is also a super important institute, Reseune, who developed the cloning technology that has been crucial to humanity's colonization of the stars. The Union is divided into several different political representations (Military, Commerce, Citizens, Industry, etc.) of which Reseune basically controls Science. The politics are roughly competition between the Expansionists who want humanity to keep colonizing space and expanding and the Abolitionists who are against cloning and expansion and the Centrists.

Reseune is led by Ariane Emory, a powerful, superior matriarch. Her advanced intelligence (technical, social and political) is demonstrated early on as well as her many enemies, including another brilliant scientist, Jordan Warrick and his son/clone Justin. Early on in the book, she is murdered. Her family and the political bloc that she represented decides to clone her and grow her replicate up in an environment as close as possible to the original one and her growth and relationship with Justin is the main part of the story for most of the book.

See, it's a lot to explain and I am really glossing over it. The issues that come up are really interesting. Do you hate the child clone of the person who totally fucked you over as an adult? How does a clone react slowly learning about their genetic mirror image and predecessor? And what are the risks of a human society that can clone itself to make beings of various skill levels and psychological stabilities? Cherryh really thinks these things through in Cyteen and it's pretty fascinating stuff. It's also really gripping. You get caught up in it and the readers emotional responses to characters get thoroughly twisted around as you learn different aspects of well-detailed characters. It won the Hugo and I think it deserved it.

Honestly, that I almost gave up on the book in the first twenty pages, I blame on the publisher. This edition had one really crappy map of the planet of Cyteen, which you don't even need. There are only two cities they visit anyways. What it needed was a political map and glossary, so you can quickly figure out who all the players are.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)